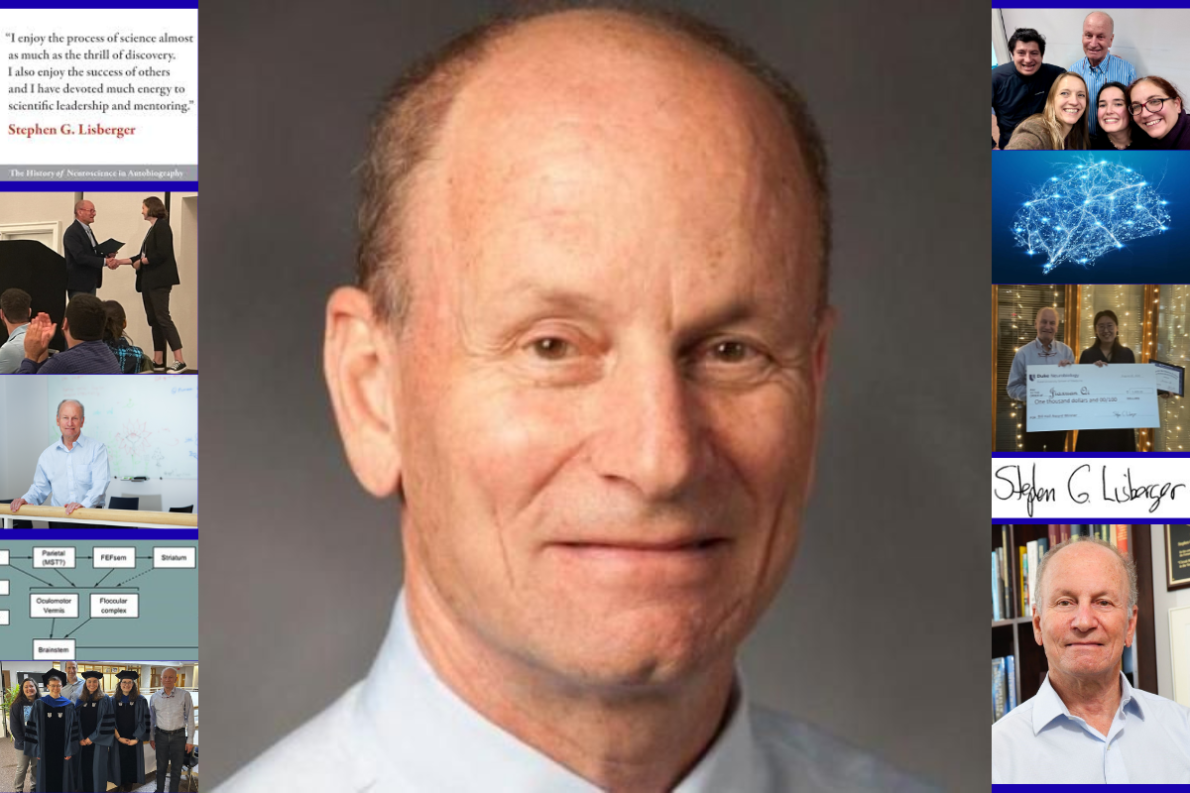

After 14 years of guiding Duke Neurobiology through remarkable growth, innovation, and change, Steve Lisberger, PhD, is stepping down as chair. Today marks both the conclusion of his tenure and the beginning of a new chapter under interim chair Staci Bilbo, PhD. During his leadership, the department expanded its research horizons, deepened collaborations, and made lasting contributions to the broader neurobiology community. To honor this milestone, we asked Dr. Lisberger to share reflections on his time as chair, the evolution of the field, and his hopes for the future. Our interview is below.

Looking back over your 14 years as chair, what changes in the neurobiology department stand out most to you?

First and foremost, two-thirds of our faculty joined Duke during my tenure as chair. They have modernized our scientific agenda, produced outstanding research, and, just as importantly, embraced the vision of Duke Neurobiology. Their commitment to collaboration and interaction has been invaluable, and they have been wonderful colleagues and friends.

Second, I like to believe that my informal approach — keeping my door open and actively participating — has helped create a true sense of belonging. We are not a collection of isolated labs, but a connected community, and that has been one of our greatest strengths.

How have you seen the broader neurobiology community shift during your tenure, and what role do you think our department has played in that?

When I was being recruited, Duke Neurobiology — an interdepartmental and interdisciplinary community — quickly became central to my vision. I saw the potential to transform the intellectual culture, and that possibility inspired me. The Department of Neurobiology has been instrumental in fostering this sense of community, thanks in large part to the strong connections built by our interdisciplinary PhD students and the primary faculty who have carried much of the responsibility for running the Neurobiology Graduate Training Program. I am deeply grateful to the other chairs in the School of Medicine, past and present, for their steadfast support and partnership. During my tenure, our seminar program has grown in both size and impact, becoming a cornerstone of Duke Neurobiology. I also extend my sincere thanks to the Ruth K. Broad Foundation for recognizing its importance and providing generous annual support.

What were some of the most rewarding or memorable moments for you as chair?

Highlights from recent years include the promotion of many of our assistant professors to tenured positions, the election of Dr. Rich Mooney to the National Academy of Sciences, and the successful revival of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center — an achievement made possible in part through Gene Washington’s Translating Duke Health initiative. Our huge graduate recruitment dinners at Parizade that reflected the richness and cohesiveness of the Duke Neurobiology community are a standout memory.

As you step down, what directions or opportunities do you see for the department’s future?

Our research encompasses several key areas of focus. Systems neuroscience — including research with non-human primates — remains central, as only a Department of Neurobiology within a School of Medicine can truly study how the brain functions in real time. Computational neuroscience is another pillar. In recent years, we’ve seen powerful examples of how collaboration between computational and theoretical experts and experimentalists creates outcomes far greater than the sum of their parts. Neurodegeneration research represents an exciting opportunity for growth, supported by recent philanthropic investments in the School of Medicine. And speaking of philanthropy, our ability to secure major gifts is essential. If we cannot raise the resources needed to understand the brain and develop knowledge-based approaches to diagnosing, treating, and curing brain disorders, then we are missing a critical responsibility.

What advice would you give to the next generation of leaders in neurobiology?

First, change is essential for growth and for keeping our community vibrant. I recommend regularly reviewing our activities and strategies, asking how we might refresh them to sustain interest and engagement.

Second, effective leadership requires presence and accessibility. Leaders should listen to all members of the community and have the courage to advocate for what is right.

Third, and not to sound trite, “showing up is 80% of the game.” When colleagues gather — whether for coffee or a seminar — connections happen, and ideas flourish. Leaders must be present and inspire others to do the same.

Finally, do not be afraid to “play outside the lines.” Innovation often begins where convention ends.